Rethinking phonological loop in working memory model: phonological divergence of the direct pathway

Introduction. Most cognitively demanding tasks require temporal storages of transient information, i.e. short-term store (STS). It is located between sensory stores and long-term stores, and used to hold and manipulate information for cognitive tasks as a working memory1. Though the dual-task study2 showed that STS was really acting as a working memory, the processing time and accuracy weren’t enough to account for working memory. As a result, it was assumed that the working memory is not simply a singular storage unit like STS, but made up of a few components.

As a new approach, while replacing the concept of the STS, Baddeley and Hitch (1974) suggested the working memory (WM) model, and it has been successful in that it could explain non-unitary feature of STS and provide more specific explanation about information transfer between short-term memory and long-term memory. According to Baddeley (2003a), there are four components of working memory, and among them, phonological loop (PL) has been investigated rigorously, with related to various language functions and its deficits.

The PL houses speech-based information and the memory trace to the PL fades after about 2 seconds. Articulatory control takes written material and converts it into a phonological code to be stored and rehearsal can re-strengthen a memory trace before it disappears. All these processes are supervised and coordinated by the central executive (CE) unit.

But, how can we accept the existence of the PL and its role in working memory? There are four psychological evidences for the PL. First, there is a phonological similarity effect. That is, errors which subjects made in remembering letter sequences tended to be phonologically, not graphematically related (Conrad, 1964). Also, sequences of phonologically related letters are harder to remember than phonologically unrelated ones, e.g. letter sequence B G V T P is harder to remember than Y H W K R (Conrad and Hull, 1964). This was also true in case of phonologically similar words, and as a result, Baddeley thought that the PL is articulatory-based.

Not all similarity is, however, detrimental for recall. On contrary, some similarity may be helpful for recall, e.g. categorized lists and rhyme of words. This is rather confusing one in that both similarity and dissimilarity benefit retention. To solve this puzzle, we should discriminate similarity and distinctiveness3. In this view, similarity only interferes with recall if it leads to confusion between the items, i.e. indistinctiveness of each item gives rise to confusion.

The second evidence is known as word-length effect (Baddeley et al., 1975). When rehearsed, shorter words are remembered better. This suggests that capacity of the PL is determined by the temporal duration and that memory span is determined by the rate of rehearsal. Also, comparing same number of words but with different length showed that word duration is the crucial variable, not number of slots. Forgetting is the joint function of trace decay and rehearsal rate, and rehearsal is successful if it is faster than trace decay.

If the subject has to produce meaningless speech (e.g. ‘the the the’) during recall task with visually presented stimuli (Articulatory suppression), the memory would decline and the phonological similarity effect would vanished. This indicates that working memory encodes visually presented verbal material into phonological code, which is a role of the PL. In other words, inhibition of subvocal rehearsal keeps articulatory loop from refreshing information from phonological store. This is supported from research with patients with brain damage (Shallice and Butterworth, 1977; Vallar and Baddeley, 1984).

The last is an irrelevant or unattended speech effect. Irrelevant speech during presentation or retention phase of a memory experiment decreases memory performance, although the subject is told to ignore it. This is evidence that auditorily presented stimuli have automatic and mandatory access to a phonological system.4 That is, the qualitative nature of sound has an impact on accessing the phonological store and disrupting memory. The irrelevant speech effect showed additive effect, interacting with phonological similarity effect in auditory presentation of stimuli, which is not observed in visual presentation (Hanley and Bakopoulou, 2003).

In summary, a simple decay hypothesis can explain the characteristics of the PL. The decay in a passive phonological store is deeply related with an articulatory process, which determines the memory performance. Additionally, the verbal material presented visually has indirect access to the PL via subvocal articulation. In this respect, the PL as well as the WM itself is not simply storage, but an active processing of transient information.

Phonological Loop Revisited

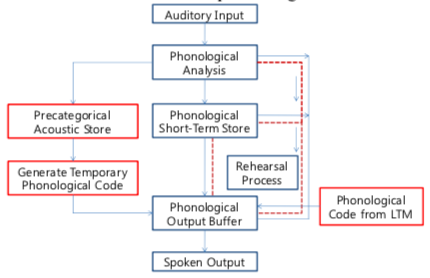

Based on the above evidences, Baddeley suggested the structure of PL as shown in Figure2.

The major feature of the PL is that there is an articulatory loop to rehearse any phonological information. It may be confused by phonological similarity or indistinctiveness, but be strengthened by clear articulation. However, this can’t account for why the articulatory suppression erases the phonological similarity effect and the word-length effect only when the stimulus is presented visually. Also, under articulatory suppression, subjects can still judge rhymes and homophony of words. This means that there must be some other storage independent of articulatory rehearsal, i.e. phonological short-term store.

In short, word-length effect reflects a control process of articulatory rehearsal, i.e. long words take longer to be rehearsed, whereas phonological similarity relies on a short-term store that is accessible by auditory stimuli or by visual stimuli having been coded phonologically. Rehearsal is not yet guaranteed in this store, and articulatory suppression weakens memory in auditory presentation and prevents phonological recoding in visual presentation. This functional dichotomy of the PL is well depicted in Figure2.5

Phonological Short-term Store

How does the phonological short-term store operate? Does it use lexical representations (words) or phonological representations (segments or syllables)? To resolve this question, we may use lexical and phonological distractors during recall task. That is, recalling sequences of digits shows almost identical performance under both phonologically similar words and auditory digits distractors, whereas it shows least disruptive performance under phonologically dissimilar words distracters. From this, we could assume that the phonological store operates at the level of individual phonemes or syllables rather than on lexical representations.

Then, how does the auditory verbal material have automatic access to language processing? The irrelevant speech effect shows the automatic access to the PL. And, according to Fodor, if any stimulus is meaningful, it is automatically accessed to the syntactic parser (Parsing is a reflex). The automaticity is very crucial feature of the PL and verbal working memory. But, how can we know whether one stimulus is language or non-language? That is, would the meaningfulness of the stimulus affect automatic access? This question would be critical issue with respect to exploring the current structure of the PL.

In a way, though the phonological short-term store is deeply related to rehearsal process, the phonological encoding process doesn’t depend on the ability to pronounce words. According to case study of anarthric patients who has subcortical motor aphasia, the PL depends on a language-based processing, not just a peripheral processing, such as speech-based one. This shows that the PL operates on a deep level of language, which is different from simple imitation of any sounds, and it also implies that the PL might be related to language acquisition of vocabulary learning.

Remained problems in Phonological Loop

There are controversial ideas about the function of PL. Among them, Baddeley et al. (1998) and Papagno et al. (1991) suggested that the PL may be more important in learning new words than familiar ones. On the other hand, Baddeley (1998) found that young children who didn’t use subvocal rehearsal could still learn new vocabulary. In spite of that, at least partially, the PL seems to be used for learning to read and acquiring vocabulary, as well as language comprehension. Especially, a correlation was found between non-word repetition and vocabulary, and this shows demanding of the PL in language acquisition.

This issue, in turn, raises the problem of discriminating language from simple sounds. Which level of the working memory model is responsible for this? What’s the difference between sounds with meanings and the others? To answer this question is not simple and especially we should consider the initial stage of processing, i.e. sensory-level processing. As previously mentioned, the PL shows modality effect, e.g. serial recall under auditory presentation is better than under visual presentation. In addition, the performance of serial recall during aloud reading is better than the one during silent reading (Conrad and Hull, 1968). All these evidences show that the modality of stimuli has an important role in working memory.

Interestingly, however, there is qualitative divergence of the performance according to the auditory stimuli during serial recall. For example, the stimulus suffix effect6 during serial recall task wasn’t observed for buzzer suffix, which wasn’t true for speech suffix. On account of this result, Crowder and Morton (1969) suggested Precategorical Acoustic Storage (PAS). According to PAS, auditory information to be remembered is stored in a relatively uncategorized code for periods of time of about several seconds, in terms of modality specific sensory memory. This could account for the modality effect, but there are still evidences against PAS theory, such as contextual modulation of suffix effectiveness, modality and suffix effect with nonacoustic stimuli or with articulatory suppression in which information in PAS is not available.

Clearly, the PAS is not enough to account for the modality and suffix effects. However, it might provide plausible accounts of discriminating meaningful sounds from pure acoustic sounds. That is, the distinctiveness of any sound may be determined by transferring of sound code from PAS to the PL at initial stage of the auditory processing.

Summary of the missing points

Despite the phonological loop accounts for many neuropsychological results in terms of working memory model, there are still missing points, especially in terms of the processing of various sounds. In view of acoustic signals, language and non-language7 have much in common. In spite of that, however, it’s clear that the PL shows different behavior according to the modality of stimuli. Consider the simplest case of repeating heard sounds. Even in case of meaningless sounds, such as environmental noise, we can mimic or imitate it. But, there is no rehearsal or automatic language processing in that case, and the PL is not deeply involved. If then, how would it be processed in terms of the PL?

The PL is fundamentally language-based and its characteristics can be summarized as follows: 1) any verbal material is automatically accessed to PL, 2) PL is not a simple speech-based articulator, but a language-based processor with specific meanings, 3) PL uses phonological codes, not lexical codes, and 4) unfamiliar words including non-word have no long-term representation and thus aren’t affected by the PL process. In this view, sounds that are not linguistic ones8 have no detail accounts and this point is unclear in the PL model.

This problem is deeply related with the old question, i.e. what is the role of phonological short-term memory? People found that patients with STM impairment have no difficulty in language understandings and spontaneous speech production (Shallice and Butterworth, 1977; Vallar and Shallice, 1990). This raised the issue that the PL didn’t appear to be crucial to either the comprehension or production of spoken language and then why do we need such a memory?

According to Gathercole, there is an extremely close relationship between the children’s phonological memory skills and their abilities to learn new phonological material. This is consistent with the previous studies form Baddeley et al. (1998) and Papagno et al. (1991), which show the relationship between non-word repetition and learning vocabulary. More specifically, she hypothesizes that adequate temporary storage of the phonological form of a novel word is the first crucial step towards building a stable long-term representation of its structure.

In this view, the PL can be understood in terms of language acquisition, especially learning of new words. Accordingly, given that there is no stored knowledge about the sound pattern to repeat, it’s forced to rely upon the temporary representation of the non-word (or unfamiliar word) in phonological store. However, the current PL can’t provide precise model of this mechanism. The only route available for non-word is the direct pathway from the phonological analysis to phonological output buffer (Figure2). In the remaining section, I’ll suggest a revised version of the PL model, while focusing on the input and output buffers.

Revised Phonological Loop

The revised PL should be able to account for what happens within verbal working memory when we repeat unfamiliar words. This is also concerned with vocabulary learning mechanism. The discrimination between language and non-language among verbal materials is not apparent at the level of working memory, but many neuropsychological results show that the PL discriminates familiar (or known) sounds and unfamiliar sounds unconsciously.

Based on this fact, we can assume that the PL has two distinct processes or neural circuits for each stimulus: one is language-based, which requires rehearsal process, and the other is speech-based, which requires simple articulation process. Fortunately, the original working memory model provides such a functional division of PL, by adding an additional route from the phonological analysis to the phonological output buffer, i.e. direct pathway. However, it’s not enough to explain how it works or what the difference between two pathways is.

To complete it, in Figure3, I suggested a revised version of PL model. It depicts the direct pathway in detail in view of unfamiliar sounds processing.

As shown before, though it has weakness as a complete theory, the concept of PAS is useful to account for how the brain deals with auditory inputs. After spectrotemporal analysis, each phonological sound is automatically stored in PAS automatically. At the same time, the phonological analysis tries to link it into the previous phonological forms, i.e. learned words. Accessed to the stored knowledge of each sound, the subvocal rehearsal process generates the phonological form from the Long-Term Memory (LTM). In this way, the PL stores internally generated phonological sequences as well as sequences of spoken stimuli.

In contrast, if failing to access the stored knowledge of the input sound, the PL including rehearsal process can’t be activated any more. Instead, the direct pathway from PAS becomes to have more crucial role in verbal working memory. Because there is no relevant phonological code for the input, the phonological code to articulate is generated temporarily, that is, we simply imitate or mimic the unfamiliar sounds without any relevant meanings. After all, whether it is accessed from the LTM or temporarily generated, the phonological code is executed in the phonological output buffer.

The essential differences between two pathways are meaningfulness and phonological codes. The direct pathway uses temporarily generated phonological codes without any meaning, whereas the indirect pathway which includes rehearsal process uses pre-stored phonological codes with relevant meanings. Those two pathways cooperate in parallel. This division of labor is verified in Yoo et al. (2009). In this study, we observed that there is auditory stimuli-specific divergence of phonological map during simple repetition tasks. According to the result, the direct pathway is mainly dependent upon the inferior frontal area, whereas the indirect pathway is dependent on the posterior parts of temporal area in left hemisphere.

Concluding Remarks

Although the new model in Figure3 provides more precise accounts for the PL, it’s still unclear how we learn new words. In addition, it is also believed that there are certainly links between reading development and the PL. That means the role of PL or verbal short-term memory should include learning of letter-sound associations (Gathercole, 1990). Thus, there are still many rooms to modify the model, especially with related to language development. In that sense, this review will provide a good starting point.

1 It indicates the modal model suggested by Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968).

2 Subject performs one task that occupies most of working memory capacity (a reasoning or judgment task) while also performing another task that relies on working memory (a memory task)

3 Mnemonic distinctiveness (…) is a property of a cue in context. It refers to the ability of a cue to access a particular target in a particular context. (Nairne, 2005)

4 Irrelevant speech and articulatory suppression show that language material has mandatory access to a phonological processor. In combinations of two effects, the additive effect is observed only in auditory presentation (Hanley and Bakopoulou, 2003). This means that it’s not caused by the decrease of general attention.

5 It presupposes two systems, i.e. inner ear (sets up a phonological representation) and inner voice (articulatory loop system). However, there is an alternative view of one system that different input leaves difference traces. In this view, there is only the difference of trace strength, i.e. weak traces (inner ear) through visual input and strong traces (inner voice) through auditory input.

6 The additional suffix in stimulus lowers performance in the recency part of the serial position curve.

7 Here, the non-language means all sounds except for language.

8 I mean, here, linguistic sounds indicate acoustic signals which have or evoke any meanings.

References

Atkinson, R.C. and Shiffrin, R.M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In K.W. Spence and J.T. Spence (eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation, 8, London: Academic Press.

Baddeley, A.D. (1998). Recent developments in working memory. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 8:2, 234-238.

Baddeley, A.D. (2003a). Working Memory: Looking Back and Looking Forward. Nature, 4, 829-839.

Baddeley, A.D. (2003b). Working memory and language: an overview. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36, 189-208.

Baddeley, A.D. and Hitch, G.J. (1974). Working memory. In G. Bower (ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation, 8, 47-90, New York: Academic Press.

Baddeley, A.D., Gathercole, S., and Papagno, C. (1998). The phonological loop as a language learning device. Psychological Review, 105, 158-173.

Baddeley, A.D., Thomson, N., and Buchanan, M. (1975). Word length and the structure of short term memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 14, 575-589.

Conrad, R. (1964). Acoustic confusions in immediate memory. British Journal of Psychology, 55, 75-84.

Conrad, R. and Hull, A.J. (1964). Information, acoustic confusion and memory span. British Journal of Psychology, 55, 429-432.

Conrad, R. and Hull, A.J. (1968). Input modality and the serial position curve in short term memory. Psychonomic Science, 10:4, 135-136.

Crowder, R.G. and Morton, J. (1969). Precategorical acoustic storage (PAS). Perception and Psychophysics, 5, 365-373.

Gathercole, S.E. (1990). Working memory and language development: How close is the link? The Psychologist, 57-60.

Hanley, J.R. and Bakopoulou, E. (2003). Irrelevant speech, articulatory suppression, and phonological similarity: A test of the phonological loop model and the feature model. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 10:2, 435-444.

Nairne, J.S. (2005). Modeling distinctiveness: Implications for general memory theory. In R.R. Hunt & J. Worthen (eds.), Distinctiveness and memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 27-46.

Papagno, C., Valentine, T., and Baddeley, A.D. (1991). Phonological short-term memory and foreign language vocabulary learning. Journal of Memory and Language, 30, 331-347.

Shallice, T. and Butterworth, B. (1977). Short-term memory impairment and spontaneous speech. Neuropsychologia, 15, 729-735.

Vallar, G. and Baddeley, A.D. (1984). Fractionation of working memory: Neuropsychological evidence for a phonological short-term store. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 23, 151-161.

Vallar, G. and Shallice, T. (1990). Neuropsychological Impairments of Short-term Memory, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Yoo, S., Jeon, H., and Lee, K. (2009). Auditory stimuli-specific divergence of phonological map in human cortical areas. Proceedings of the Korean Society of Cognitive Science, 88-94, May 15-16, Seoul, Korea.